1 September Sunday New Delhi

|

| Humayan's Tomb & Bijou |

|

| Mort with Taj Mahal |

No true picture of our travels or state of mind during them can be conveyed without a word about hotels and choosing them. We have had guidebooks for each country. But their descriptions are usually sketchy and often out of date. Some airports have useful hotel reservation services, but again it is a blind choice. Brochures and such are little help. If we were staying at 1st class places, no problem, most are alike. But we want cheap, clean, with convenient location, acceptable comfort. Often, it is too much to ask.

In Kathmandu we asked RNA to telex reservations at a hotel which sounded right in our book. When we arrived, they had not received the word — the only room left was a suite at $14.50. It was a plain, uninspiring place to live. We stayed one night then went to the YMCA guest house— nicer, a bit less $ but far away from the center of things. Finally, we came to the Palace Hotel, one block away from the first choice, drab but clean room, no towel or hot water: $7. We took it, checked out (stealing 2 towels) and checked in. All this was a full morning’s work.

|

| Gallery Of Art sculpture |

2 September Monday New Delhi

Another early rising day. During those years of work— waking 5 days a week at the same time to the alarm, it had seemed to me to be one of the signs of freedom to be able to wake when I chose. Yet, here I am waking more often than not around dawn— to the alarm ... to catch a train, taxi to an early flight, or just so as not to miss the sunrise, or as today, to catch a 7 am tour bus.

As it was, it was worth it. There were several things to see, scattered all over the city, which we would never have had the energy to do on our own. Janter Mantra, an observatory in the manner of Stonehenge; India Gate (“No Arc de Triomphe” Bea shrugged.) Humayun’s Tomb, a Moghul Emperor’s, the architecture of which formed the idea for the Taj Mahal, we are told. Qutb Minar, a 238 foot minaret and victory tower built by the Moslem Moghuls to signify their victory over the Hindus. They ruled India for 800 years and built the most beautiful structures in the world.

In the afternoon we visited Ghandi Memorial, simple quiet, peaceful. Jama Masjid, another giant mosque, in Old Delhi amidst bazaars and beggars and near the imposing Red Fort. Later we spent exhausting hours booking flight, fighting with cabbies.

3 September Tuesday New Delhi to Agra to Delhi

I guess this has to be called a travel day, we sure traveled. Again rising near dawn. Our bus took 5 hours to cover the 200 miles to Agra, the same back. But I have never spent a more worthwhile day.

We rode through the Indian countryside past factories and farms from horizon to horizon. It was all there: the animals— water buffaloes, oxen, goats, camels, elephants; the bullock carts, bicycles, wagons. The villages. The people— women taking water from wells and carrying their jugs on their heads. The goatherds. The boys bathing with their buffaloes. The men plowing behind the oxen. The mud huts. The irrigation canals. The road on which we rode was the same used for centuries from Delhi to Agra by kings and merchants, pilgrims and travelers in caravans.

In Agra we finally saw it— the Taj Mahal. And what can I say— it is simply the most perfect and beautiful looking thing (building or anything else built by Man) I have ever seen. It is perfectly symmetrical. Pure white with inlaid stones, set apart from everything. Its back against a wandering river. Just something you can look at forever and never tire.

So this is India— you can be philosophical and say the beauty is a tomb, a monument to death and therefore just as mordantly symbolic of India as the smell of decay in the streets of Calcutta and maybe it is a truth. But it is only a country, with a rich history and culture and art, drawn from many cultures, trying to make a go of it in a modern world with which it has in common the desire to progress to a good life. Its ascetic religious philosophy has defined “Good Life” as simple, pure, holy.

So this is India— you can be philosophical and say the beauty is a tomb, a monument to death and therefore just as mordantly symbolic of India as the smell of decay in the streets of Calcutta and maybe it is a truth. But it is only a country, with a rich history and culture and art, drawn from many cultures, trying to make a go of it in a modern world with which it has in common the desire to progress to a good life. Its ascetic religious philosophy has defined “Good Life” as simple, pure, holy.  |

| Delhi-Agra Road |

4 September Wednesday New Delhi

We spent this day in a shopping and buying frenzy and it left both of us irritable and feverish, literally.

Shopping in Chandni Chowk was fun, because we decided early on what and for who and how much we were going to buy and were helped to a “wholesale” merchant of cloth and wool hand embroidered shawls which Bea says are excellent. The salesmanship was low-pressure, well-mannered and we were served tea, milk and biscuit. Later, we paraded Connaught Circus, carping at each other in the oppressive heat. Tonight we ate at Moti Mahal on fish and chicken— excellent. We met an Israeli couple shell shocked on their first day in India. We felt like old, wise travelers.

5 September Thursday New Delhi to Bombay

The contrasts of India are very evident here— what is beautiful good and pleasant, and what is ugly, evil and unpleasant. We checked out early and tried to get a taxi, several of which were near our hotel, to take us the few blocks to the Indian Airlines office where our airport bus was waiting. In every city in Asia, the taxi customs differ. In Delhi there are meters but the drivers try to set flat rates. Many refuse to go by the meter at all, especially on short trips. We have haggled and by and large, have gotten our way. But now we were over a barrel with our bags to shlep and bus to catch. We paid through the nose and it started our day on a sour note.

We carried the bags off the taxi, painfully dragged them to our waiting area and later dragged them again in the stifling heat to our bus. A porter picked them up and put them in the luggage compartment a few feet away. After we got in, he came round and demanded 50p for each bag for everyone on the bus. One Indian became indignant, seeing in the practice all that is wrong with India. “People expecting pay for doing little or nothing.”

Another passenger was an absurd looking Westerner: he wore a white sun hat over his shaved head, a red shirt and sarong, sandals. He was hefty and hairy-armed but had the manner of a sad “faigele.” Later we chatted with him. He was on his way to an ashram to study yoga. He showed us the mosquito net he’d gotten and offered us a Dunhill. He was an Australian and called the porters “Johnnie.” As he paraded through the terminal, he got stares from Indians and Westerners— he was a very unlikely person.

The flight was routine, hampered only by the worry of going into a city without hotel reservations. In Delhi we had spent the good part of an afternoon trying to get Pan Am, Indian Air, or a travel agent to help us. Pan Am referred us to India Air, who shrugged, a travel agent would only help if we wanted a 4 or 5 star hotel. India government office was polite but no help.

|

| Agra box |

After a 45 minute ride through and around the “suburbs” and the city—which has several peninsulas and harbors— we were in the vicinity of our Y. This I knew from following the landmarks on our map. But the driver couldn’t find it. He would stop for directions, each time a cabbie, doorman or cop would chatter in Hindi and point and he would drive and fail to find the street—which is a major thoroughfare in the heart of town. After 3 or 4 of these stops, I got out and stopped a passerby and by prodding and urging we finally found it.

The cost was $3.00 which I angrily paid, though trying to be philosophical—ever try to get a cab in the rain in NY? The Y room was a delight: clean, airy modern and with continental breakfast which cost the same as the dive in Delhi. We relaxed, then consulted our guidebook: the Taj Hotel, nearby, had a buffet lunch for $2.50, it said. Also in that hotel was a Pan Am office and government tour office.

We set out. Architecture was English, the streets crowded with auto traffic implying affluence, shops of all kinds were enticing, there were the usual calls to change money or to help, some begging children and some raggedy men sleeping in doorways. But nothing like Calcutta or even parts of Delhi. It was only mildly annoying. We found the Taj Hotel easily—we could hardly miss it—a tall Miami type luxury hotel on the harbor near Gateway to India Arch. We strolled through the terrazzo floored lobby and took the lift up to the ballroom. By its elegance and quiet we could see we were in financial trouble.

We took a menu from the captain’s desk. The fare was expensive Indian and Continental. At the front we could see the large columned room. The price was not enticing: 28 rupees, with tax the total for the buffet was about $9 for two. We moaned and so did our stomachs; our stomachs won.

Buffets are always intimidating. You want to get your money’s worth and there are so many good looking things set out—you want a little of everything and you end up stuffing yourself and enjoying it less—maybe a metaphor for world travel. Of course the pastries were a fabulous special treat for both of us—we were tempted to stuff a few in Bea’s huge purse. The knowledge that the leftovers from the diners here could feed half the city was a bit disconcerting and the vapid string orchestra playing benign waltzes and reels added to the aura of unreality.

Bea became furious with me when I complained about the experience and resorted to her well-worn hyperbole: “You always struggle over making a decision, then always regret it and never enjoy the experience you chose!” I became angrier because ... it always hurts when it strikes the mark, and too deeply, especially from her, someone— the only one I care anything about what she feels about me. Which of course I didn’t say—didn’t even get at the time. We let the moment pass, but it was on our chests as much as the pastry.

Now stuffed and logy, we went to Pan Am and had to leave our precious air tickets so they could see about our desire to go to Kabul—there was doubt about whether it could be done without extra cost, and we would have to wait until 4. It was now 2 p.m. and we decided to nap. We had spent a restless night. We both still suffer coughs from our lingering colds and the past days have caused increasing tensions between us.

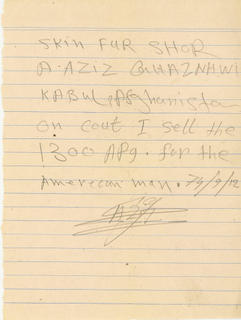

Bea fell asleep and I read until 4. I dressed and let her sleep. I went out to do our chores. I went the same way to the hotel, being accosted only a few times, seeing a man in rags compete with a pigeon for nuts fallen from a vendor’s roaster, and another whose wracking cough brought phlegm to a hole in his throat. At Pan Am after another bout with the dim-witted worker I got the tickets for Kabul. It meant a 7 A.m. flight on IA back to Delhi and then a 1330 Afghan Air flight to Kabul. Monday would be dreadful, but ... The clerk was annoyed but agreed to try to reserve a hotel room for us there.

I then changed money at Cooks—I could get a better rate on the black market but I am paranoid about that. I have never been “smart” about money. I bought some Indian cigarettes and inquired at the tourist desk for the Elephanta Caves tour. The caves are sculpted Hindu Gods on an island across the harbor. Boats leave every morning from Gateway Arch—except during monsoon season—when they often don’t go at all—May to mid September.

So again our timing is awful. It has become clear what we suspected before we came to Asia—this was the absolute worst time of year to travel. The intense heat and humidity are draining, the rains depressing (as in Kathmandu), difficult. It is off season for tourism, which is a plus in some ways: easier to get hotel room, rates are lower. But empty restaurants are often dreary, and waiters with no one else to wait on are annoyingly attentive. Transport and activities are curtailed. Add that to the usual difficulties of any travel and especially in the East— strikes, like the one of Air India; and international politics—which prevented our visits to Taiwan and Korea. We still worry about Turkey / Greece / Egypt / Israel on that score.

Plus the rigors of suitcase life, the close quarters and being together constantly, with the ever present money worries, and our different personalities, all these have added to the tensions between Bea and I. It has opened old salved over wounds caused by our differences, now sore and bleeding.

It is of course a test and we are today at a low ebb, but we can muddle through and survive and are determined to do it.

After my jaunt I fell into a coma-like sleep and was only dimly aware of Bea’s insistent call for food. I put her off—“in an hour, Okay?” ... “another ten minutes” ... Then I finally admitted that I would rather sleep than get up and traipse about looking for another cheap meal in a dingy restaurant. Bea demurred, but after a while—during which I immediately fell asleep—she insisted on eating.

I grudgingly stirred, whining all the way. This annoyed her. She dressed in a huff and stormed out alone. At first, I was angry enough to let her go, if that’s the way she felt. But soon my conscience woke me up and I went out after her. The streets were dark and filled with strange faces. I became frantic with concern for her safety ... and my loneliness ... after what must have been only a few minutes but seemed to me to be much, much longer. Bea with her white pink skin, light hair and long thin body has been an attraction everywhere in Asia, especially here in India, with children, other curious women and particularly the men who already have a fascination with Western women as proved by the many advertisements pointedly using them to sell everything.

I found her at a greasy spoon open air restaurant nibbling at a yellow sandwich and sucking on a lime. I sat with her and groggily chatted. She was sore as hell, but I think a little relieved that I had come. I ate some salty fried fish—they had a big menu but only fish and coffee were available.

We got into a conversation with a man from Ceylon who was stuck in Bombay trying to get to Teheran. We had the same problem—prevented from doing it by the Asian Games there, which made accommodations scarce. He was going to Europe to stay with friends in Berlin. He worked in the tea business and had lived for some time in East Africa. We talked about food. They eat locusts, grasshoppers, roaches in Africa which he had tried. He seemed somewhat shocked that the French eat snails and frogs legs. In a Masai village he stopped short of drinking the local thirst quencher: milk and cow blood. It turned out he was also staying at the Y. We all strolled back together.

Bea fell asleep before we could resolve our spat and I stayed up to finish Maugham’s “The Razor’s Edge” which has always had something to say to me in an unreal, romantic way.

A note on Hinduism: I have been studying as much as I can about it and talking about it with as many people as I can. It is a remarkable religion—in its complexity it is all things: a faith, a world view, a philosophy, a psychology, an ethos, a mythology. It allows for intellectuality, mysticism, spirituality. It is dark, joyous, witty and somber. It is ascetic and sexual. It is strongly symbolic but provides concrete idols to worship. It contains a panoply of Gods, each with traditional functions and personalities, yet at its heart is monotheistic or in some modes, pantheistic. It is distinctively Indian, but has survived by absorbing the beliefs of many other sects and other major religions. To the pious it provides a faith in eternal peace and a satisfactory if tortuous means of attaining it. To the casual or even agnostic Hindu it provides a sense of community with holidays and festivals, an identity in its rituals, and justification of a way of life.

In my examination it seems to be a perfectly fine religious system. Then why is the country in which it is practiced so fucked up?

Does the religion which defines the value system hold responsibility for the society it serves and influences? Or maybe there is nothing “wrong” with India fundamentally. Maybe it is merely “backward” because by accident of history, climate, or geography, it joined the “modern” world too late. Am I putting too much stock in my own ideas of “The Good Life”? If Hinduism is right, then life on earth is the hell and will always be so even with our comforts and “progress” which are only superficial and transitory and obstacles to the search for true “Goodness” and Peace of Mind.

6 September Friday Bombay

A few words about food. When traveling to different countries a major interest for us is eating the local foods. In the States we were used to some Asian foods: Chinese of course, Japanese, and even Indian “style” cuisine. But eating is always an adventure, a sample of local customs which reflect to some extent the personality, degree of wealth, the eccentricities of each place.

Some friends who had preceded us on similar trips advised that Asia is for buying, Europe is for eating. I am sure this is true; as Bea insists that nothing compares to French cooking, even in the commonest of kitchens. Of course, Italian food we know and love. Perhaps these foods will not be as strange, exotic or adventurous as the foods we have eaten in Asia, just as Europe itself is less alien to our experience.

Tonight we strolled along a broad cool avenue to a restaurant where we ate a meal in a style which was new to us, even here in India. We were brought various vegetarian dishes served in metal bowls on a silver metal tray, a “thali.” (Phonetic spelling, to my ear.) There are light breads and rolls called “puris”. You tear a piece and dip into a bowl with your fingers and eat. You must only use the right hand (awkward for me) since by custom this is the clean one. The waiter hovers and refills your bowls. He leaves a pitcher of water because the dishes are spicy. At the end he dumps rice on your tray if you wish and you pour the leftovers in the rice, mix it together and eat with your fingers. So now we have eaten with chopsticks, spoons, spoon and fork, and hand.

I have also noticed a definite difference in the rice served in the countries we have visited; though it is the staple of all— the grains somehow all seem a little different, whether from the type, or the preparation, I don’t know. I remember reading that sushi chefs in Japan study for rice for a year as part of their education. The rice here seems particularly hardy, rich and fluffy when at its best.

We must rest now because we are stuffed like little pigs.

7 September Saturday Bombay

It is funny how days that begin inauspiciously have often ended with our best experiences. This day we began listless, without much ambition. We have been at low tide for a few days now; our energies seemingly drained. We have slept away huge chunks of days and lain in bed reading and dozing for hours. It is partly our colds which linger annoyingly, the ever present heat which causes malaise and the let down of spending our last days in India.

We decided quickly that Bombay had not much to offer—it is a bit prettier, its architecture a bit more exotic, new skyscrapers, art deco apartments, cathedral like public buildings. It has a harbor, the usual hectic smelling bazaar, a great deal of traffic on its wide avenues; but not much of the tension of the other cities. Of maybe it is there but we have simply gotten used to it. Even the child beggars here seem better fed, their hearts not really into their pleas.

We supped continental dinner, lobster thermidor, and strolled back ready to read—I bought and began “War and Peace” of all things to read on holiday! Then we got into a 2½ hour discussion about Hinduism, Sikhs, prejudice, travel, etc., with two young Indians: the guy who is the night clerk and a young woman who is an engineer. It was friendly, funny and informative. They were intelligent, witty, tolerant, worldly, fine people.

It reinforced my notion that there is nothing particularly mystical or threatening about India. The people are different only in custom and superficial mannerisms; but they want the same things, have the same frustrations, prejudice and ignorance about the way things are and ought to be. It gave me a much warmer feeling for the country and people than our first impression.

I guess that is why India is so “difficult” to figure out. You have to “get past” the first and most vivid negative impressions in order to see more deeply into the vast complexity and discover—not The truth—but other truths.

8 September Sunday Bombay

We have spent our last full day in India in an enjoyable and worthwhile way, visiting Elephanta Caves on an island 6 miles from Bombay. They contain sculptures of Hindu Gods which are chiseled from the solid basaltic rock of a mountain in the 6th or 7th centuries. As a monument it is in the category of the Taj Mahal, the Gold Buddha of Bangkok and the Great Buddha in Nara (which was created around the same era) in awesomeness and achievement.

All four are interesting to me because of the effect they have—and were meant to have—on the viewer: respect, for the skill of the artisans, sure, but more, respect for the power and wealth of the patron religion or ruler which ordered its creation. Imagine the impact over the Ages of the visitors to the shrine of the Gold Buddha, 52 tons of gold, in a society which is poor beyond our conception. The huge statue in Nara in the solemn shrine must have inspired enormous awe at the power of such a symbol.

Ironically, the Taj Mahal is the most awesome because of its intrinsic “artistic” beauty, but also because it is a tomb, a shrine to one dead person in a world in which millions live in anonymity. As a romantic symbol by a man of enormous wealth, power and arrogance created as a monument to a woman he loved, a miraculous extravagance.

9 September Monday Bombay to Delhi to Kabul

Today we believed that our flying luck had finally run out, after so many flights, including those on exotic airlines like Indonesian, Royal Nepal, and now Indian Air.

Our jet taxied to the runway at Bombay airport and sat there in stifling heat for what seemed like an eternity. The cabin temp felt like it pushed way over 110̊ as we sat, without cabin air conditioning, either because of a malfunction or in prep for take-off. Peering from my seat in the second row through the open cockpit door, I could see no planes ahead of us in a cue which might cause such a long delay and for a long time there was no explanation.

The Indian businessman across the aisle sat in his business suit trying to look business like reading his wilting newspaper while stains of sweat darkened the collar of his shirt.

|

| Janter Manter detail |

Suddenly the pilot announced that there was a “slight mechanical problem” and that it was nothing to be alarmed about and that it would be repaired shortly. A ramp appeared at the doorway and a workman climbed the steps and entered the cabin. He wore Indian Air overalls and carried a toolbox. I watched as he entered the cockpit and kneeled on the floor behind the pilot. He unscrewed a plate, and began to probe what looked like wires and cables.

After another long period, during which I watched Bea closely for signs of faint, my attention was jerked toward the cockpit by a loud “clank, clank” sound. The workman was on his knees pounding with a hammer at the works under the plate. My eyes became huge.

After a short time, he rose and left. The stewardess closed the door behind him. I expected her to tip him. The engines whirred and we began to move.

I held Bea’s hand tightly and kissed her fingers. I told her I was glad we had this brief time together and that I hoped we would spend eternity in a cool place.

We grasped our hands until we landed in New Delhi.

Now we only had to survive our next flight on Afghan Air to Kabul.

We found that our flight was canceled, and we had to wait for hours in the airport for a seat on the next one.